Voter turnout in local elections in Norway

Lower voter turnout than Sweden and Denmark

Published:

This article was first published in Norwegian, in Statistics Norway’s journal Samfunnsspeilet: Kleven, Øyvin (2015): Valgdeltakelse i lokalvalg i Norge. Bak Sverige og Danmark i valgdeltakelse. Samfunnsspeilet 2/2015. Statistisk sentralbyrå.

The next municipal and county council elections are due to be held on 14 September, and for the first time in Norway’s voting history, the number of eligible voters will exceed 4 million. Voter turnout in local elections has been falling in Norway and most of Europe in recent decades. Four years ago, however, the number going to the polls in Norway increased, from 62 to 65 per cent. The share of the Norwegian electorate that exercises its right to vote is still lower than for our Scandinavian neighbours, and particularly Sweden.

In the last parliamentary election, voter turnout was 78 per cent; an increase of two percentage points from the parliamentary election in 2009. After the elections on 14 September, we will be able to see if the trend of recent decades is turning towards a steady increase. However, in this article, we must make do with examining voter turnout in previous elections.

Under the provisions of the Election Act (Valgloven), there is no specific turnout rate that needs to be achieved in order for an election to be declared valid. However, there is a widely-held view that a democracy needs a certain degree of engagement and participation in order to safeguard its long-term survival. There is a concern that political decisions are not considered legitimate when politicians have only been elected by a small number of voters. Concern has also been expressed for the legitimacy of decisions where participation does not represent all sections of society (see Klausen 2005 for an overview).

Lower turnout for local elections than parliamentary elections

At the last municipal elections four years ago, voter turnout rose by three percentage points, from 61 to 64 per cent (total result for municipal and county council elections was 64.5 per cent, with 64.2 and 59.9 per cent respectively). These local elections were held in the shadow of the terrorist attacks of 22 July. The perpetrator had a political motive for the killings and many saw his acts as an attack on Norwegian democracy. One of the responses to the attack was therefore to support democracy by participating in the elections (Berg and Christensen 2013).

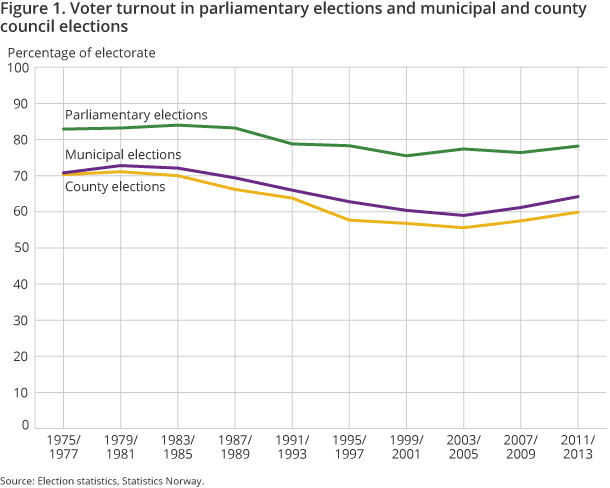

Voter turnout is consistently higher in National Assembly elections than in local elections, both in Norway and the rest of Europe. Turnout in municipal and county council elections has always been lower than in parliamentary elections. The county elections have the shortest history and the lowest voter turnout. These elections started in 1975 and are held at the same time as the municipal elections.

Comparisons of voter turnout between local elections (municipal elections), regional elections (county elections) and national elections (parliamentary elections) must take account of the fact that the eligibility criteria are not the same for all elections. In parliamentary elections, only Norwegian citizens have the right to vote, while foreign nationals who have lived in Norway for at least three years and Nordic nationals who are resident in Norway can vote in municipal and county council elections. In the upcoming elections in September 2015, foreign nationals make up about 8 per cent of the electorate.

In the period from 1975 to 2013, voter turnout fluctuated between 84 per cent at the parliamentary election in 1985 to 56 per cent at the county elections in 2003. The lowest turnout in municipal elections was in 2003, when only 59 per cent of the electorate voted. The last time more than 70 per cent of the electorate turned out at local elections was in 1983.

Norway around the European average

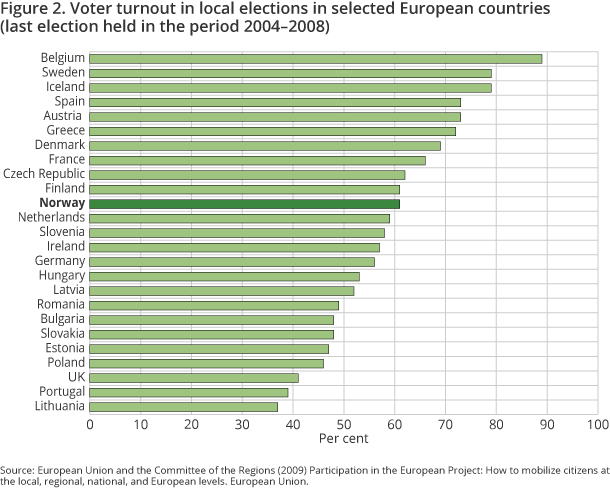

In contrast to national elections, there are no readily available European databases with information on local elections. It is therefore more difficult to compare voter turnout in local elections than in national elections in Europe. Based on data collected by the EU some years ago (2004-2008), we see that Norway’s turnout was roughly average compared with the rest of Europe (see Figure 2). This tendency has also been shown in earlier periods (Klausen 2005). In Belgium, voting in elections is mandatory. Unsurprisingly, Belgium has the highest voter turnout in Europe, with 90 per cent, but even there around 10 per cent of the population do not vote. Sweden and Iceland are also high on this ranking, with almost 80 per cent voter turnout in local elections. At the bottom is the UK, Portugal and Lithuania, where turnout is around 40 per cent.

There are considerable variations in how local and regional elections are held throughout Europe. Some countries, such as Norway, hold the municipal and county elections on the same day. Other countries, such as Germany and the UK, hold municipal elections in different years for the individual regions. If Norway were to follow this electoral system it could mean a city council election being held in Oslo on 14 September 2015 and a municipal council election being held in Bærum on 7 February 2016, for example.

Figure 2 shows average figures for local elections held in various federal states and regions in countries such as Germany and the UK. At the other extreme, Sweden holds its local elections at the same time as its National Assembly elections.

There has been discussion about holding national, regional and local elections all on the same day in Norway, but a number of objections to this have been raised. The concern is that the dominance of national politics over municipal politics would become even greater, and local issues and local debates would be pushed into the background (Klausen 2005:368). There are also significant variations in how easy it is to join the electoral roll – the register of eligible voters. In Norway, a person is automatically included if they meet the voting criteria, whereas, in the UK for example, voters need to actually register themselves on the electoral roll.

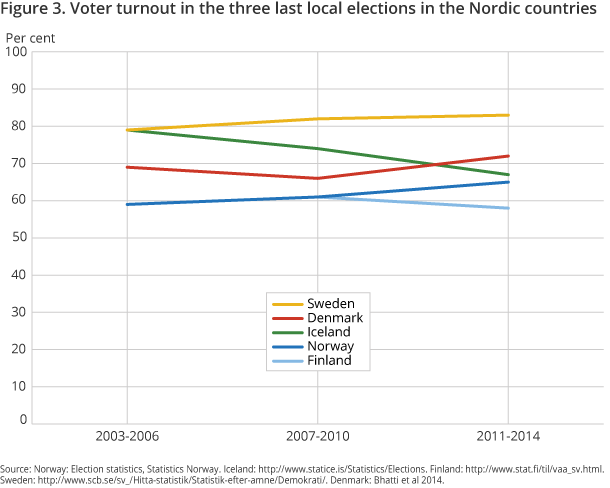

Second lowest turnout in the Nordic region

Comparisons of Norway and other Nordic countries show that only Finland had a lower turnout than Norway in the last local elections. In Finland, the turnout was 58 per cent at the last local elections in 2012. Since Sweden has the highest voter turnout in Europe, it also therefore has the highest turnout among the Nordic countries; 83 per cent at the last local elections in 2014. Denmark, whose election system is roughly the same as Norway’s, was about seven percentage points higher than Norway in the last local elections in 2013. Iceland has had a negative trend; their top ranking in Europe less than 10 years ago has slipped to almost the same level as Norway, with a 67 per cent turnout in the last local elections in 2014.

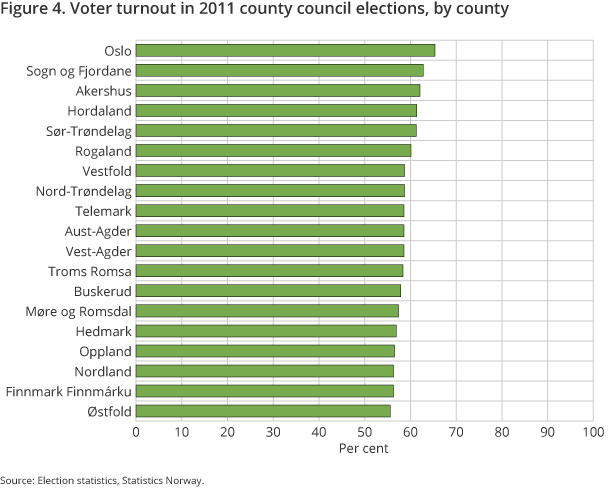

Sogn og Fjordane – highest turnout in 2011 county elections

The overall voter turnout in the 2011 county elections was 60 per cent. Oslo leads the way with 65 per cent (see Figure 4). However, these figures are not fully comparable with county elections in other counties since the elections in Oslo are not county council elections as such, they are city council elections and district council elections. Excluding Oslo, Sogn og Fjordane has the highest turnout, with 63 per cent, and Østfold, Nordland and Finnmark are the lowest, with 56 per cent each; a difference of seven percentage points. Akershus, Hordaland and Sør-Trøndelag are also among the counties with the highest turnout in county council elections.

Voter turnout in the last four county elections since 1999 (Table 1) shows a similar trend. Oslo, Sogn og Fjordane, Akershus and Hordaland are consistently high, while the counties Østfold, Nordland and Finnmark are relatively low.

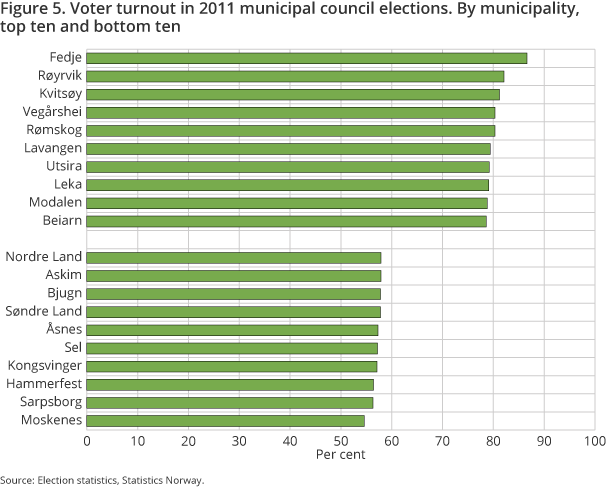

Large variation between the municipalities

Municipal and county council elections consist of more than 400 different elections for different municipal councils, district councils and county councils. Voter turnout varies considerably between the municipalities, much more so than among the counties (see Figure 5). In Fedje, 87 per cent of the electorate voted, while in Moskenes the corresponding figure was about 55 per cent; a difference of 32 percentage points.

In the 2011 municipal elections, the county with the highest voter turnout was Sogn og Fjord, with 68 per cent. Østfold had the lowest turnout with 61 per cent; a difference of seven percentage points in the county breakdown. Turnout in local elections is relatively high in the populous counties Hordaland, Sør-Trøndelag, Oslo and Akershus. There is no clear geographic profile of voter turnout levels.

Active member of society?

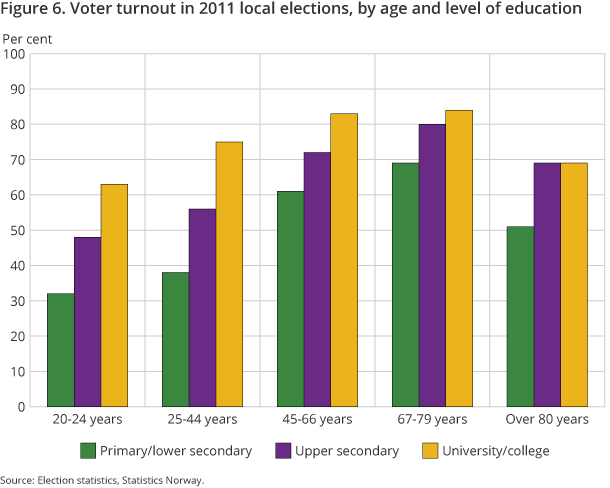

In the literature on voter turnout (see Aardal 2002 for an overview), political resources are cited as a major reason why some people vote and some don’t. The correlation is straightforward: the higher a person’s social status and the more integrated they are in society, the more likely they are to vote (Aardal 2002: 24). This so-called integration perspective on political participation is linked to the degree of integration as a member of society. For example, the workplace is an important arena for political awareness and learning (Sigel 1989). When a person retires from working life, they no longer have the formal contacts they once had. Furthermore, as people age their family situation changes; children move out, spouse dies, etc. We have therefore identified an inverted U-shape when examining voter turnout by age.

The conventional view of the elderly and voter turnout suggests that turnout decreases when a person retires from working life and wants to ‘enjoy their retirement’. However, this hypothesis ignores the fact that those who retire have undergone a political socialization and that political engagement has become a part of their personality. Analyses of time series regarding age and voter turnout show that turnout is relatively high among pensioners, and only starts to fall when they reach 80 (Berglund 2005, Kleven 2005, Berglund and Kleven 2010).

The literature also shows that voter turnout has a correlation to education. However, as far back as the early 1960s, disparities in voter education were shown to be more closely correlated to education in the USA than in Norway (Rokkan and Campbell 1970). In Norway, many of those with a lower education were members of groups and organisations that had close links to political parties, which in turn meant they were mobilised to participate. Thus, there is not necessarily a direct correlation between low education and low political participation.

Women with a higher education are most likely to vote

In recent elections in Norway, the trend has been for women to participate to a greater extent than men. Sample surveys conducted by Statistics Norway in connection with elections show that the turnout tends to be a few percentage points higher among women (see Table 2). However, this is ambiguous when controlling for other indicators, such as age and education. In relation to age, the voter turnout has an almost inverted U-shape; a relatively low level for the youngest group, rising for the middle aged and falling again among the oldest group. This concurs with the so-called integration hypothesis; those who are most integrated into society will also show the greatest tendency to vote in elections.

Young people who are still living at home and not yet part of working life are less likely to vote than those in employment. Another group that is generally not in employment, is the oldest group, and here we also see a lower voter turnout. First-time voters (18-19-year-olds) are more likely to vote than those in their early 20s. School elections and the focus on first-time voters are no doubt part of the explanation for this. Another factor is that when young people are in education they often do not live in their home municipality, which can make it difficult for them to vote.

Research on elections shows that education is an important factor in explaining voter turnout. We see a clear correlation between level of education and participation in elections. Among women and men with a higher education, eight out of ten vote, while among those with a lower level of education, the figure is only five out of ten (see Table 2).

Figure 6 shows voter turnout by education and age. We see that the age effect (the inverted U-shape) also applies here, with the youngest voting the least in every level of education. In the youngest age group (20-24 years) with a primary or lower secondary education, the turnout is 32 per cent, while the corresponding share in the group aged 45-79 years is approximately 84 per cent. The disparity in turnout based on education level is greatest for the two youngest groups. This may be an indication that Norway could end up in a situation similar to that of the USA, for example, where there are major disparities in voter turnout according to education.

Only three in ten foreign nationals voted in 2011

At the elections in 2015, around 310 200 foreign nationals will have the right to vote. This represents 8 per cent of the electorate, compared with 6 per cent in the previous local elections in 2011. The largest group of foreign nationals entitled to vote was the Poles, accounting for 18 per cent of foreign nationals. Swedes were the second largest group with 13 per cent. However, only around three out of ten foreign nationals actually exercised their right to vote in 2011 (Table 3). Norwegian citizens are therefore twice as likely to vote as foreign nationals.

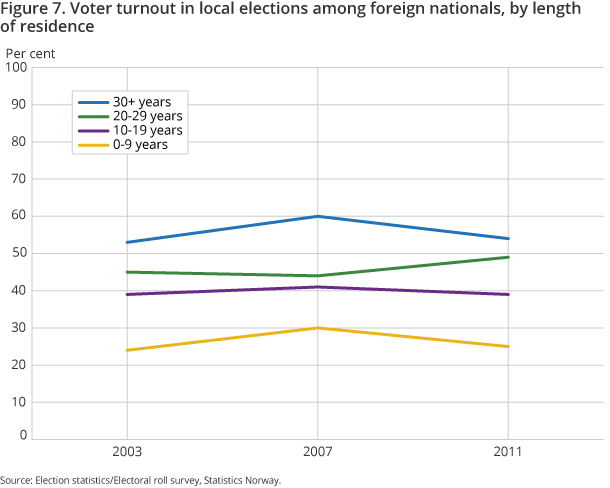

Voter turnout among foreign nationals increases with length of residence

Voter turnout among foreign nationals increases with length of residence (see Figure 7). For those who have been in Norway for over 20 years, the turnout is significantly higher than for those who have been here less than 10 years. This has been the trend in the last three local elections. For those who have been in Norway for 30 years or more, voter turnout is on a par with that of Norwegian citizens.

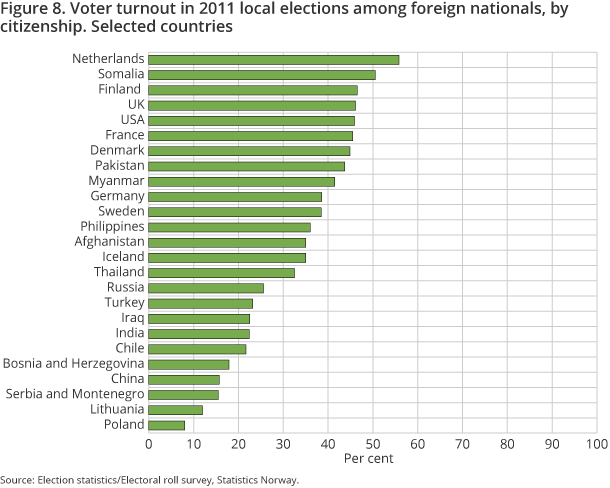

Large variation among foreign nationals

Voter participation is lower among virtually all foreign nationals than Norwegian citizens. This is also a feature we see in most other European countries, i.e. the country›s own citizens are more likely to vote than the foreign nationals in local elections (see for example Bhatti et al 2014). In the 2011 election, Dutch citizens had the highest turnout, with 56 per cent, and around half of the Somalis exercised their right to vote. The turnout for Polish citizens was just 8 per cent (see Figure 8).

Bibliography

Berg, Johannes and Dag Arne Christensen (eds.) (2013) Et robust lokaldemokrati – lokalvalget i skyggen av 22. juli 2011 (A robust local democracy – local elections in the shadow of 22 July 2011). Abstrakt forlag. Oslo.

Berglund, Frode (2005): «Alt ved det gamle? Om eldre og politikk» (“All about the elderly? The elderly and politics”), Norsk Statsvitenskapelig Tidsskrift 1, vol. 21.

Berglund, Frode and Øyvin Kleven (2010) «Politisk deltakelse blant seniorer. Engasjerte borgere med svak representasjon» (“Political participation among senior citizens. Engaged citizens with poor representation”) in Eilif Mørk (ed): Seniorer i Norge 2010, Statistical Analyses 120, Statistics Norway. http://www.ssb.no/sosiale-forhold-og-kriminalitet/artikler-og-publikasjoner/seniorer-i-norge-2010

Bhatti, Yosef, Jensd Olav Dahlgaard, Jonas Hedegaard Hansen and Kasper Møller Hansen (2014) Hvem stemte og hvem ble hjemme? Valgdeltakelsen ved kommunevalget 19. november 2013. Beskrivende analyser af valgdeltagelsen baseret på registerdata (Who voted and who stayed at home? Voter turnout at the municipal elections on 19 November 2013. Descriptive analyses of voter turnout based on register data). CVAP Working Paper Series 2/2014. Centre for Voting and Parties, Department of Political Science. University of Copenhagen.

European Union and the Committee of the Regions (2009) Participation in the European Project: How to mobilize citizens at the local, regional, national, and European levels. European Union.

Klausen, J.E. (2005). «Kan deltakelsen i lokalvalg økes?» (“Can participation in local elections be increased?”) In Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning.

Kleven, Øyvin (2005): «Politisk deltakelse blant seniorer» (“Political participation among senior citizens”), in Elisabeth Ugreninov (ed): Seniorer i Norge, Statistical Analyses 72, Statistics Norway. http://www.ssb.no/sosiale-forhold-og-kriminalitet/artikler-og-publikasjoner/seniorer-i-norge

Rokkan, Stein and Angus Campbell (1970) “Citizen Participation in Political Life” In Stein Rokkan (ed.): Citizens, Elections, Parties. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistik-efter-amne/Demokrati/

Sigel, Roberta (1989): Political learning in adulthood. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

http://www.stat.fi/til/vaa_sv.html

http://www.statice.is/statistics/population/elections/

Zhang, Li-Chun, Ib Thomsen and Øyvin Kleven (2013) “On the Use of Auxiliary and Paradata for Dealing with Non-sampling Errors in Household Surveys” in International Statistical Review (2013)

Aardal, Bernt (2002): «Demokrati og valgdeltakelse – en innføring og oversikt» (“Democracy and voter turnout – an introduction and overview”), in Bernt Aardal (ed): Voter turnout and local democracy, Oslo: Kommuneforlaget.

Contact

-

Statistics Norway's Information Centre